Birds consistently have more neurons packed into their small brains than are stuffed into mammalian or even primate brains of the same mass. That’s according to a study published June 13, 2016 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that systematically measured the number of neurons in the brains of more than two dozen species of birds, ranging in size from the tiny zebra finch to the six-foot-tall emu.

Neurons, specialized cells that conduct electrical impulses, are the basic data processing units, the ‘chips’, of the brain.

Vanderbilt University neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel is a senior author of the paper. She said in a statement:

For a long time having a ‘bird brain’ was considered to be a bad thing: Now it turns out that it should be a compliment.

The new study suggests an answer to a puzzle that comparative neuroanatomists have been wrestling with for more than a decade: how can birds with their small brains perform complicated cognitive behaviors? From a statement from Vanderbilt University:

The conundrum was created by a series of studies beginning in the previous decade that directly compared the cognitive abilities of parrots and crows with those of primates. The studies found that the birds could manufacture and use tools, use insight to solve problems, make inferences about cause-effect relationships, recognize themselves in a mirror and plan for future needs, among other cognitive skills previously considered the exclusive domain of primates.

The new study suggests that birds can perform these complex behaviors because birds’ forebrains contain a lot more neurons than previously thought – as many as in mid-sized primates’ brains. Herculano-Houzel said:

We found that birds, especially songbirds and parrots, have surprisingly large numbers of neurons in their pallium: the part of the brain that corresponds to the cerebral cortex, which supports higher cognition functions such as planning for the future or finding patterns. That explains why they exhibit levels of cognition at least as complex as primates.

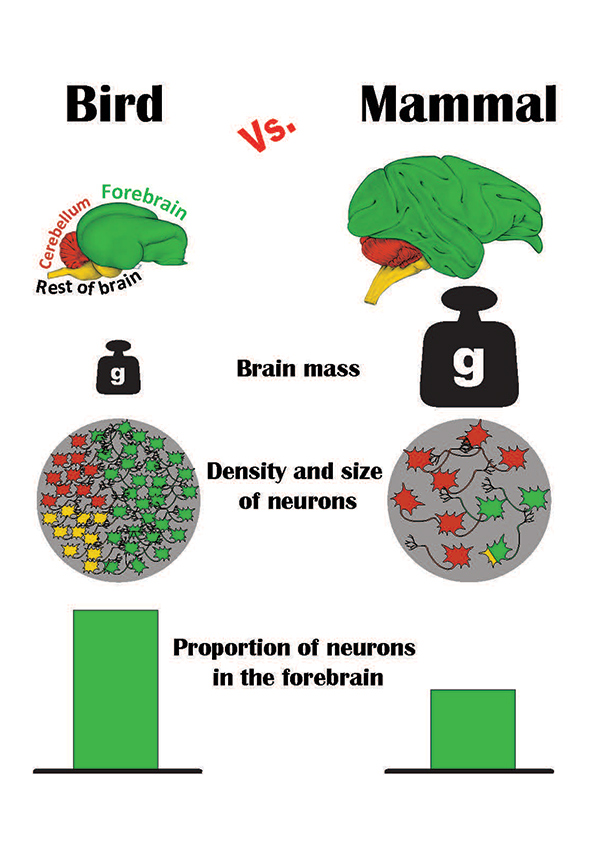

What makes that possible is that the neurons in bird brains are much smaller and more densely packed than those in mammalian brains, the study found. Parrot and songbird brains, for example, contain about twice as many neurons as primate brains of the same mass and two to four times as many neurons as equivalent rodent brains.

Not only are neurons packed into the brains of parrots and crows at a much higher density than in primate brains, but the proportion of neurons in the forebrain is also significantly higher, the study found. Herculano-Houzel said:

In designing brains, nature has two parameters it can play with: the size and number of neurons and the distribution of neurons across different brain centers, and in birds we find that nature has used both of them.

Herculano-Houzel acknowledges that the relationship between intelligence and neuron count has not yet been firmly established, but she suggests that bird brains with the same or greater forebrain neuron counts than primates with much larger brains might provide the birds with much higher “cognitive power” per pound than mammals.

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Bottom line: A study published June 13, 2016 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that birds consistently have more neurons packed into their small brains than are stuffed into mammalian or even primate brains of the same mass.