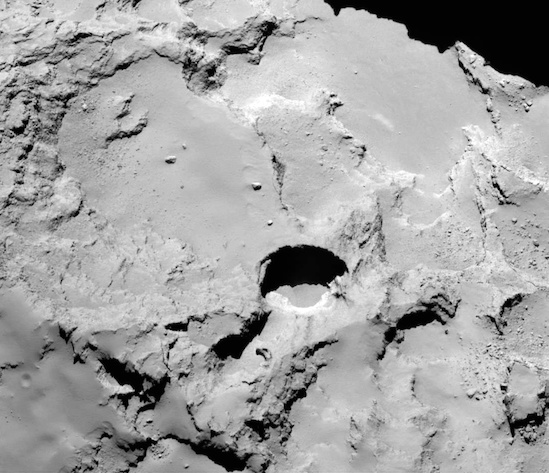

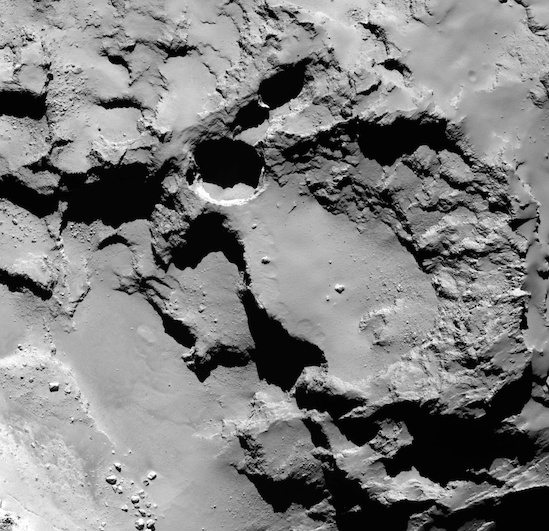

Scientists announced this week (July 1, 2015) that several surprisingly deep, almost perfectly circular pits on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko – which has been orbited by ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft since August, 2014 – may be sinkholes. In a way that tells us that nature operates in a similar way across the many worlds in our solar system, these pits may be formed in much the same way as sinkholes on Earth. On Comet 67P, though, the sinkholes form when ices beneath the comet’s surface sublimate, or turn directly to gas, as the comet gets closer to the sun. The study appears in the July 2, 2015, issue of the journal Nature.

The pits are large, ranging from tens of meters in diameter up to several hundred meters across. There are two distinct types of pits: deep ones with steep sides and shallower pits that more closely resemble those seen on other comets, such as 9P/Tempel 1 and 81P/Wild. Jets of gas and dust can be seen streaming from the sides of the deep, steep-sided pits – a phenomenon not seen in the shallower pits. Astronomer Dennis Bodewits at the University of Maryland, a co-author on the study, commented in a statement:

These strange, circular pits are just as deep as they are wide. Rosetta can peer right into them.

Sinkholes occur on Earth when subsurface erosion removes a large amount of material beneath the surface, creating a cavern. Eventually the ceiling of the cavern will collapse under its own weight, leaving a sinkhole behind.

Bodewits and other astronomers on his team used Rosetta observations to create a model for the formation of the possible sinkholes on Rosetta’s comet. The comet has been drawing nearer the sun throughout the time that the spacecraft has been orbiting it. Its perihelion – closest point to the sun in its 6.5-year orbit – will come on August 13. As the comet draws closer to the sun in its orbit, it warms. Ices in the body of the comet – primarily water, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide – begin to sublimate. These astronomers say that the voids created by the loss of these ice chunks eventually grow large enough that their ceilings collapse under their own weight, giving rise to the deep, steep-sided circular pits seen on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Their statement explained:

The collapse exposes comet ices to sunlight for the first time, which causes the ice chunks to begin sublimating immediately. These deeper pits are therefore thought to be relatively young. Their shallower counterparts, on the other hand, are most likely older sinkholes with more thoroughly eroded sidewalls and bottoms that have been filled in by dust and ice chunks.

Similar circular shapes have been found on the surface of other comets. But, over the comets’ thousands and millions of years in space, those pits have been filling in by new material. On the other hand, on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, scientists think they are seeing freshly formed pits.

A total of 18 pits have been seen on the surface of 67P. None located near where ESA’s Philae lander – part of the Rosetta mission – set down last November. Scientists are still trying to re-establish a steady communications link between the newly revived Philae and the Rosetta orbiter.

The European Space Agency officially extended the Rosetta mission last month, which means that the spacecraft will have the opportunity to track Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko as it reaches its closest point to the sun and then begins moving away. The extension expands the mission by nine months, from the planned end date of December 2015 to September 2016.

The extra observational time will enable the team to see how the comet’s surface responds to decreasing solar radiation.

Read more: Rosetta team struggles with Philae link

Bottom line: Scientists say that deep, almost perfectly circular pits on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko may be sinkholes. Sinkholes on Earth happen when a subsurface cavern collapses. On the comet, the caverns may be created by ices turning to gas, as the comet nears the sun.