Best New Year’s gift ever! EarthSky moon calendar for 2019

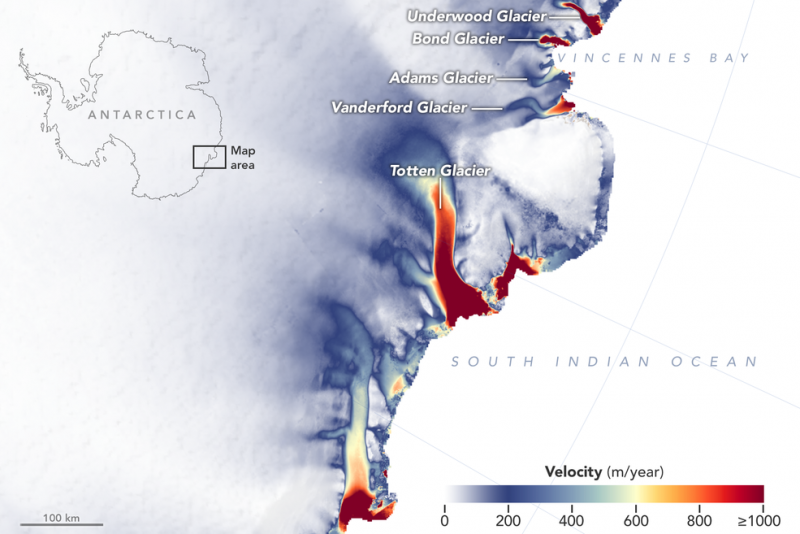

In recent years, researchers have warned that East Antarctica’s Totten Glacier, an enormous ice sheet with enough ice, scientists say, to raise sea levels by at least 11 feet (3.4 meters), appears to be retreating, thanks to warming ocean waters. Now, researchers have found that a group of four glaciers sitting to the west of Totten, plus a handful of smaller glaciers farther east, are also losing ice.

Although ice loss in East Antarctica has the potential to reshape coastlines around the world through sea level rise, scientists have long considered it more stable than its neighbor, West Antarctica. Now, new maps show that a group of glaciers spanning 1/8 of East Antarctica’s coast have begun to melt over the past decade, hinting at widespread changes in the ocean.

Catherine Walker, a glaciologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, has been studying glacial retreat in East Antarctica. Walker presented her findings at the American Geophysical Union meeting in Washington in December 2018. She said in a statement:

Totten is the biggest glacier in East Antarctica, so it attracts most of the research focus. But once you start asking what else is happening in this region, it turns out that other nearby glaciers are responding in a similar way to Totten.

For her research, Walker used new NASA maps of ice velocity and surface height elevation. She found that four glaciers west of the enormous Totten Glacier, in an area called Vincennes Bay, have lowered their surface height by about 9 feet (2.7 meter) since 2008. Before that year, there had been no measured change in elevation for these glaciers.

Farther east, a collection of glaciers along the Wilkes Land coast have approximately doubled their rate of lowering since around 2009, and their surface is now going down by about .8 feet (.24 meters) every year.

These levels of ice loss are small when compared to those of glaciers in West Antarctica. But still, they speak of nascent and widespread change in East Antarctica. Alex Gardner is a glaciologist with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. He said in a statement:

The change doesn’t seem random; it looks systematic. And that systematic nature hints at underlying ocean influences that have been incredibly strong in West Antarctica. Now we might be finding clear links of the ocean starting to influence East Antarctica.

For her study, Walker used simulations of ocean temperature from a model and compared them to actual measurements from sensor-tagged marine mammals. She found that recent changes in winds and sea ice have resulted in an increase to the heat delivered by the ocean waters to the glaciers in Wilkes Land and Vincennes Bay. She said:

Those two groups of glaciers drain the two largest subglacial basins in East Antarctica, and both basins are grounded below sea level. If warm water can get far enough back, it can progressively reach deeper and deeper ice. This would likely speed up glacier melt and acceleration, but we don’t know yet how fast that would happen. Still, that’s why people are looking at these glaciers, because if you start to see them picking up speed, that suggests that things are destabilizing.

There is a lot of uncertainty about how a warming ocean might affect these glaciers, due to how little explored that remote area of East Antarctica is. The main unknowns have to do with the topography of the bedrock below the ice and the bathymetry (shape) of the ocean floor in front of and below the ice shelves, which govern how ocean waters circulate near the continent and bring ocean heat to the ice front.

For example, if it turned out that the terrain beneath the glaciers sloped upward inland of the grounding line – the point where glaciers reach the ocean and begin floating over sea water forming an ice shelf – and featured ridges that provided friction, this configuration would slow down the flow and loss of ice. This type of landscape would also limit the access of warm circumpolar deep ocean waters to the ice front.

A much worse scenario for ice loss would be if the bedrock under the glaciers sloped downward inland of the grounding line. In that case, the ice base would get deeper and deeper as the glacier retreated and, as ice calved off, the height of the ice face exposed to the ocean would increase. That would allow for more melt at the front of the glacier and also make the ice cliff more unstable, increasing the rate of iceberg release. This kind of terrain would make it easier for warm circumpolar deep water to reach the ice front, sustaining high melt rates near the grounding line.

Bottom line: New research suggests that more glaciers in East Antarctica are losing ice due to warming oceans.